Photo credit: CAN Borneo

Photo credit: CAN Borneo

Ah…another International Orangutan Day has arrived. I can’t remember precisely how many years ago that we at Orangutan Land Trust along with other orangutan conservation organisations around the world created International Orangutan Day to heighten awareness about orangutans. But this year, as I embarked on writing this piece, I had to ask myself, “What can I say this year that I haven’t already said for so many years running?” I sought inspiration from one of our lead Scientific Advisors, who offered me some ideas that ran along the lines of all the things that are going wrong in orangutan conservation and have been for some time. I replied that I was looking for something “a bit more upbeat” to celebrate the day. And here, my articulate and insightful friend found himself stumped. Nonetheless, via a chat app, we challenged ourselves to dig deeper for ideas, some of which I will share here.

What IS working in orangutan conservation?

Long-term committed management in orangutan habitat fragmented by oil palm works, as demonstrated in particular by the work being done in the Kinabatangan landscape in Sabah. This undertaking by palm oil growers and NGOs to improve connectivity for orangutans, elephants and other species can be said to be the jewel in the crown. But currently, this cannot be taken to scale easily because there are neither enough NGOs nor is there enough funding.

Citizen science

What IS especially needed for upscaling is new approaches in management from government, businesses and communities. Citizen science is an effective emerging tool in the conservation of orangutans. Borneo Futures have lead the way in developing and piloting this biodiversity monitoring tool for agribusiness. They’ve been collaborating with an Indonesian palm oil company which has over 1200 active citizen scientists who have, thus far, recorded over 125,000 wildlife observations. “The resulting data is of high enough quality to guide conservation management. This approach could save companies significant time and money in comparison to traditional methods where small teams of conservation specialists attempt to record species data for large areas. More importantly, this method invites personal interest in conservation and makes company staff proud to play a role in biodiversity management.”

The importance of real biodiversity monitoring in plantations

The importance of real biodiversity monitoring in plantations cannot be over-emphasised. Sadly, very few companies go beyond simply marking whether orangutans (or other species) are present (or absent). But you cannot manage on the basis of absence and presence. I.e., if something was present during the HCV assessment and then at some stage becomes absent, you are too late to intervene by definition. Hence the importance of quantitative monitoring. This is possible with techniques like camera traps, but much cheaper using citizen science.

Quantitative monitoring of orangutans

Quantative monitoring of orangutans means that dependable and accurate biodiversity valuation can take place. The above company has commissioned biodiversity valuations for three of their estates so far. One of their estates (with orangutans) has a value of $197 million. This is the value that biodiversity in that estate contributes to society over a 30-year time-frame. Certainly incentive for a grower to manage and, if possible, enhance their HCV areas! A long cry from the early days of oil palm expansion in places like Borneo, where bounties were paid on the heads of dead orangutans. Another positive change for orangutans is that there is less oil palm expansion resulting in less deforestation and habitat loss in Indonesia.

Oil-palm driven deforestation

There has been a significant decline in oil-palm driven deforestation in Indonesia over the last several years, but it did start to rise again in 2023. The biggest gains to be made for orangutans are in areas that have been allocated for oil palm development but not yet converted. If CSPO companies develop these areas, there will have to be large set asides. If conventional oil palm runs the show, it can be assumed that they will just clear the forest, unless the government prohibits this. Despite declining rates, deforestation does remain a critical issue, not only for oil palm but for other activities (notably mining of nickel and other substances).

“Palm-oil free”

New research on the role of sustainable palm oil in meeting global vegetable oil demand underlines yet again that choosing sustainable palm oil is a better option for the future of orangutans than going “palm free.” The latest IUCN report, Exploring the Future of Vegetable Oils, the authors showed that oil demand is growing and needs to be met. Palm oil currently has to play a role because of its lower land requirements. Fortunately, there is now such thing as deforestation-free palm oil and if growers adhere to RSPO standards, then any expansion should avoid deforestation. Avoiding deforestation in orangutan habitat regions is, of course, paramount to their survival.

Guidance of leading conservation experts

A personal and non-scientific assessment of media and social media seems to indicate that companies and consumers are increasingly adopting the guidance of leading conservation experts and organisations to choose sustainable palm oil over a blanket boycott. Orangutan Land Trust is particularly active in using social media and traditional media to bring nuance to the discussion of sustaianble palm oil and its role in protecting orangutans. We’ve noted a marked decrease in the number of tweets, for example, that urge people to boycott palm oil to save wildlife – mostly only one account holder and her 3-4 devoted followers who retweet the same handful of misinformed tweets daily. We see far more posts on social media exploring the idea of sustainable palm oil as a solution. We believe a lot of this is down not to just our outreach but the outreach done by a number of zoos, NGOs, academic instutions and credible individuals like Dr Jane Goodall.

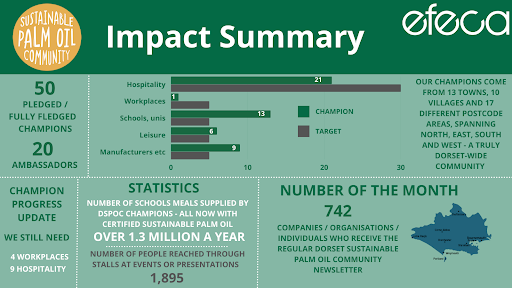

Sustainable Palm Oil Communities

The Sustainable Palm Oil Communities campaign led by Chester Zoo continues to go from strength to strength. More and more companies and institutions are signing up, Jane Goodall has endorses the Dorset Sustainable Palm Oil Community and outreach events are regularly held. I recently visited my local zoo, Twycross Zoo, where an animatronic orangutan drew in visitors of all ages to learn about orangutans and sustainable palm oil. Newquay Supports Sustainable Palm Oil continues to bring together zoos, schools, universities and businesses, a campaign supported by none other than Sir David Attenborough.

Palm oil pledge

Other NGOs are also doing their part to encourage people to choose sustainable palm oil to save orangutans. The Borneo Orangutan Survival Foundation has created a “Palm Oil Pledge” urging people to sign on to “Encourage more businesses to use sustainably sourced palm oil by increasing the demand for it” and “Show your commitment to support palm oil farmers who have put sustainable farming practices in place.”

Celebrities on palm oil

A new campaign by Rewriting Earth and Make My Money Matter, with partners Global Canopy and Global Witness, called Saving Jane is endorsed by Jane Goodall and Peter Gabriel (Gabriel recorded a piano version of his hit ‘Red Rain’ especially to accompany the video.) The campaign intends to encourage pension companies not to invest in projects that destroy climate-critical forests, and wreak havoc on the lives of people who depend on these precious ecosystems. This underlines the importance of the financial sector’s role in driving out deforestation and biodiversity loss. “Ozi, Voice of the Forest,” an animated film produced by Leonardo DiCaprio & Mike Medavoy, is being released in cinemas this month. This is the story of Ozi, an orphan orangutan who uses her influencer skills to save her forest and home from deforestation. We hope that this film will help raise awareness about the plight of the orangutan, but more importantly, drive people to take action.

What ISN’T working in orangutan conservation

So what ISN’T working in orangutan conservation? Or is, at least, not working as well as we’d like? Some ongoing practices are not as effective as we once thought they would be. For example, removing orangutans from one landscape and transferring them to another is not always the best solution for orangutans found in fragmented or degraded areas. Certainly there are cases where individual orangutans would almost certainly die if such an intervention does not take place, and transfer to a rescue centre or alternative location may be necessary, if only in terms of the welfare of that animal.

Julie Sherman

However, according to a report by Julie Sherman, et al. in Journal for Nature Conservation in 2020, “Welfare and conservation outcomes of removing wild orangutans for translocation have been little studied despite regular use. The potential risks to released animals’ welfare and to the conservation of resident wild populations are high, and the current practices of ad hoc release site selection and of releasing orangutans into viable wild populations do not meet IUCN guidelines to avoid endangering wild conspecifics. Studies are urgently needed to determine translocated orangutan welfare and survival rates, and impacts to resident conspecifics and rescue habitats. Similarly, further study of longer term impacts of ex-captive orangutan reintroductions/reinforcements are needed to understand welfare impacts and effectiveness in establishing self-sustaining viable populations.”

Accommodate wild orangutans where they are found

At Orangutan Land Trust, guided by research and data from our Scientific Advisory Board and beyond, we have long argued that the first goal in the conservation of orangutans in areas impacted by human activities is to find ways to accommodate these wild orangutans where they are found. While we do offer some funding to support the rescue of orangutans in very dire circumstances, unlike many other orangutan NGOs, we believe that driving practices and policies and supporting initiatives that protect and enhance orangutan habitat, allowing the orangutans to remain in situ is the best use of our efforts and our limited funding. Our funds also support community engagement, education and outreach, conservation research, fire-fighting and prevention and peat and forest restoration, amongst other activities. But more funds are desperately needed if we are to continue to make a real difference.

Funding critical activities in the field

Our !% for the Planet partners, most notably long-time supporters GoodLight Natural Candle, help to ensure that we can continue to fund critical activities in the field. Two recipients of this funding are CAN (Conservation Action Network) Borneo and Borneo Nature Foundation. Our collaboration with CAN Borneo has helped to encourage the establishment of five village forests in East Kalimantan as part of efforts to recognize the rights of communities to the forests around them so that orangutan protection and habitat conservation efforts can be implemented at the grassroots level. These five village forests are located along the Kelay River basin to protect 23,000 hectares of habitat for 186 orangutans, whose ecosystems consist of lowland forests and karst areas. This collaboration involves supporting the local economy around these areas by working together to develop sustainable plantations and tourism, including creating products with economic value in the market. This is done to reduce the conversion rate of orangutan habitats.

Our collaboration with Borneo Nature Foundation

Our collaboration with Borneo Nature Foundation in Central Kalimantan also helps to encourage and support community members to develop sustainable income sources, including permaculture and aquaculture initiatives, and to adopt peat-friendly land management practices. Five villages have continued to engage with BNF’s sustainable livelihoods programme in the Sebangau region, monetising a wide range of activities from honeybee cultivation to basket weaving. We also supported BNF’s efforts to build firefighting and patrol capacity. This included a network of eight community-led firefighting and patrol teams with 135 firefighters throughout the Sebangau region. Thanks to the dedicated and collaborative effort of the National Park authorities, CIMTROP and the community firefighting teams patrolling the forest and extinguishing flames, the Sebangau National Park experienced no primary forest loss.

How can you help?

There is still a great deal of work to be done and a great deal of funding needed to do it. But we can all play a part, with or without money. Individuals can choose sustainably produced products and encourage companies and governments to put a stop to those products that are linked with deforestation. All stakeholders along the supply chains of commodities coming from Indonesia and Malaysia need to commit to NDPE (No Deforestation, No conversion of Peat, No Exploitation), including financial institutions. Efforts like the ones I’ve described have shown that it can be done, but if we are to save the orangutan, these efforts need to be scaled up enormously, and soon. Join us in being part of the solution.

Photo credit: CAN Borneo

Photo credit: CAN Borneo